with our monthly newsletter.

Around the world, refugee resettlement has been a bigger and more politically prominent question in recent years than at any time since World War II. In the United States, there is research on how over time refugees become well integrated into society and how they fare in the economy. Less attention, however, has been focused on the employer side of the resettlement story: What is the experience of businesses that hire refugees?

To investigate this question, the Fiscal Policy Institute conducted over 100 in-depth interviews with refugees, employers of refugees, refugee resettlement agency staff, other service providers, researchers, and other members of the community in four geographic areas of the United States where significant numbers of refugees have resettled. The research was also put in context and guided by FPI’s analysis of data from the American Community Survey (ACS) and the Worldwide Refugee Processing System (WRAPS).

This study identified two clear ways employers benefit when they broaden their hiring pool to include refugees:

1) Refugees tend to stay with the same employer for longer than other hires.

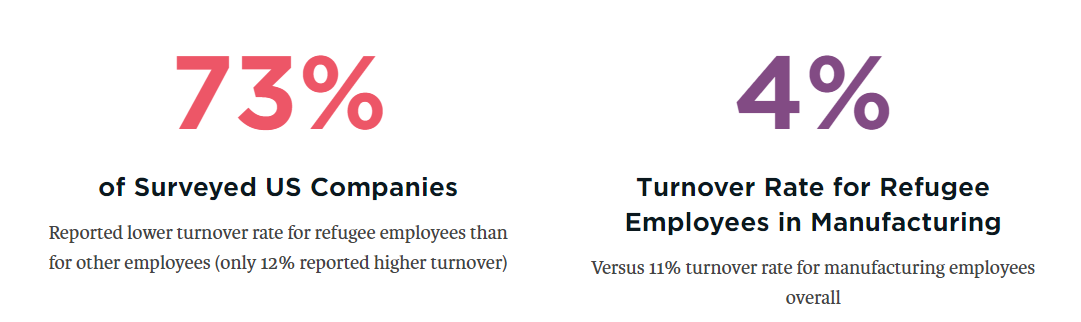

Nineteen of the 26 employers surveyed—73 percent—reported a higher retention rate for refugees than for other employees. This was consistent across industry sector, and across geography.

Among employers who gave the Fiscal Policy Institute confidential access to internal data, refugees had a turnover rate that was seven to 15 percentage points lower than for the overall workforce. Among the four manufacturing firms for which we have data, the average rate was four percent for refugees, compared 11 percent for employees overall—a difference of seven percentage points. In the hotel industry, an industry with much higher overall turnover, the rate in the job categories typically filled by refugees was 29 percent for refugees and 36 percent overall—also a difference of seven percentage points. In meatpacking, a tough occupation where retention is at least as challenging as in hotels, the differential in the firm for which we have internal data was 15 percentage points—annual turnover was 25 percent for refugees and 40 percent overall.

To put it a different way, the turnover rate for refugees was between a fifth and two thirds lower for refugees than for employees overall.

What seemed important to achieving lower refugee turnover was that the employer made at least some effort to integrate refugees into the workplace. These were not generally big investments, but they did include an attempt to address the challenges of making a place for workers from a different kind of background than their previously typical employees.

The firms where refugee turnover was about the same as or even lower than for all workers were generally the ones with turnover rates that were higher for all workers than the industry average, where service providers talked about firms using refugees as “cannon fodder” in a cycle of high burnout and replacement of workers.

Lower turnover is valuable for any business. A 2012 study by Heather Boushey and Sarah Jane Glynn found that replacing a worker typically costs businesses about one fifth of the worker’s annual salary. For a full-time worker earning $13 an hour, which is typical in our surveys, that translates into $5,200 per year saved for every worker who does not have to be replaced, and lower recruitment costs for new hires. That’s a cost savings to the employer that leaves room for investment in translation services, help with transportation, or other ways of easing refugee integration into the workplace.

Lower refugee turnover seemed to reflect a positive experience for the refugees as well. There is a larger question about options for good jobs in today’s labor market, but within that context, low refugee turnover seemed almost always a sign of comparatively positive work experience for refugees, not simply a measure of an inability to change jobs.

2) Once employers create a positive relationship with the first few refugees it opens the door to recruitment of many others.

The first time an employer hires one or several refugees, there is almost always a period of mutual accommodation. Some issues are likely to come up that have never arisen before and may take employers by surprise, though they are often also easily manageable. Language is a central challenge for new employers of refugees, and often in a way that is different than with other immigrant groups. Where training videos may be available in Spanish, for example, the same is not likely for speakers of Karenni, one of several Burmese languages.

Companies that make the effort to work these issues through, however, are often doubly repaid in both retention of the employees themselves and also in recruitment of other refugees. This recruitment advantage works at least three ways: First, when employers work through integration issues for a particular ethnic group, they’re very likely to see other refugees from that same community applying for jobs at their company. Second, as employers build relationships with refugee communities and refugee resettlement agencies, hiring logistics because easier and more efficient — if an employer works through the initial logistics of hiring refugees from one country of origin, hiring from a second group is often far easier. Finally, having already been extensively vetted by the U.S. government, refugees rarely have trouble passing the pre-employment screenings that frequently keep other applicants from getting a job.

Employers frequently felt they had learned and grown from the experience of integrating refugees in ways that made them not just better employers of refugees, but better employers in general. Making production goals and evaluation clear to people who don’t speak English well also benefited native English speakers who found the new communications clearer. An openness to hiring employees who may need training on the job has widened the door for both refugees and non-refugee employees, compared to looking for people who walk in the door with all the skills needed for a job. In some cases, hiring refugees helped the companies connect with local markets, where they were located in areas with high concentrations of refugees.

This article was written by David Dyssegaard Kallick and Cyierra Roldan for www.tent.org and was republished with permission.

with our monthly newsletter.